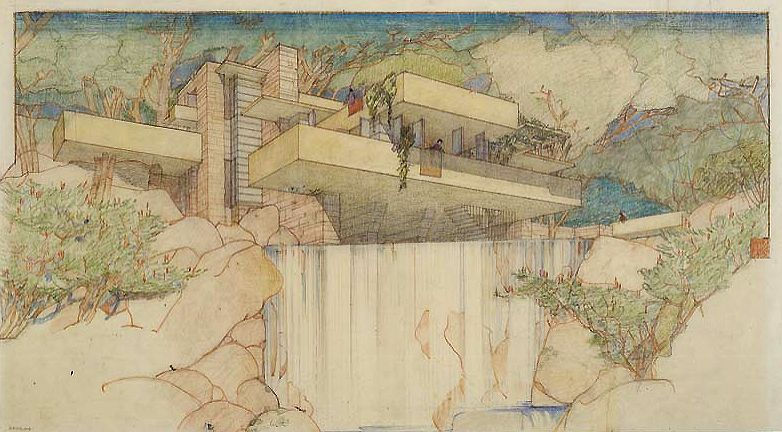

Frank Lloyd Wright’s legacy has become synonymous with awe-inspiring architecture. Over the course of his seventy-year career, Wright commissioned 1,114 architectural projects, 532 of which were realized. Perhaps his most extraordinary accomplishment is Fallingwater. Dubbed “the best all-time work of American architecture” by the American Institute of Architects, Fallingwater is an engineering marvel and modernist icon. Suspended by cantilevers over a thirty-foot waterfall, Wright’s innovative design integrates the natural world with the ambiance of upscale living. This visionary work ascended Wright to international fame and cemented his place as one of the greatest American architects of all time.

Frank Lincoln Wright was born on June 8, 1867, in Richland Center, Wisconsin. The son of two teachers, Wright was immersed in academia from a young age and took particular interest with the study of transcendentalism. Wright familiarized himself with the works of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Walt Whitman, and developed a deep appreciation for the natural world, particularly the Midwestern meadowlands he called home. Transcendentalist tenets were unquestionably influential as the budding architect incorporated them into his design philosophy of “organic architecture.” Following his parents’ divorce in 1885, Wright adopted the middle name ‘Lloyd’ to honor his mother’s maiden name.

In 1886, Wright attended the University of Wisconsin and served as a special student under civil engineer Allan Darst Conover. Unhappy with the work, he dropped out after two semesters and moved to Chicago where he began his career in architecture. He found temporary employment at the office of Joseph Lyman Silsbee before receiving a full-time apprenticeship under famed architect Louis Sullivan, who specialized in Victorian Gothic and Queen Anne styles.

Wright married his first wife, Catherine Lee “Kitty” Tobin, on June 1, 1889. The following year, he was promoted to head draftsman of Sullivan’s firm. Despite his rapid ascension to occupational prominence, Wright was constantly in debt (which he later attributed to his extravagant spending habits). To generate more income, Wright secretly accepted commissions independent of Sullivan’s firm, which violated the terms of his contract. Sullivan eventually discovered these disingenuous undertakings and confronted his young apprentice. An altercation ensued, resulting in Wright’s departure from the firm.

In 1893, following the termination of his apprenticeship, Wright established his own private practice. This newfound commercial autonomy allowed the talented protégé to experiment with architectural design and philosophy and pioneer his own artistic vision. It was with his first independent commission, the William H. Winslow House, that Wright unveiled his signature “Prairie Style”—which emphasized open spaces, strong horizontal lines, low-sloping roofs, and natural materials. This revolutionary structural design was eagerly embraced by Wright’s contemporaries and is considered a landmark development in the history of modern American architecture.

In 1903, Wright designed a house for Edwin Cheney, an electrical engineer from the affluent community of Oak Park, Illinois. While working on the project, Wright became acquainted with Edwin’s wife, Mamah Borthwick Cheney, and the two struck up a peculiar friendship. Two years later, their relationship became romantic. As Wright’s popularity as an architect grew, so did knowledge of the affair. Pretty soon, the immoral romance headlined newspapers and tabloids as the “scandal of Chicago.” In October 1909, Wright and Mamah eloped to Europe, leaving their respective spouses behind. There the two lovers remained for almost a year. During that time, Edwin granted Mamah a divorce; however, Kitty refused to divorce Wright.

While touring Europe, Wright presented his work portfolio to Ernst Wasmuth, a book publisher based out of Berlin, Germany. Wasmuth agreed to publish over one hundred of Wright’s lithographic drawings and designs in a collection titled Studies and Executed Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, more commonly known as the Wasmuth Portfolio (1910). This was Wright’s first major exposé. The publication particularly had a profound influence on European architects following the devastation of World War I and is often referred to as the “cornerstone of modernism.”

Wright and Mamah returned to Chicago in October 1910, only to be greeted by the scorn of urban socialites. Apparently, popular opinion of the affair had not changed during their year abroad. Looking to escape social ridicule and resume his architectural practice, Wright purchased a tract of land in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and built a secluded retreat called Taliesin.

Wright’s longing for peace and solitude would be met with tragedy on August 15, 1914. While Wright was working in Chicago, Julian Carlton, a chef at Taliesin, set fire to the residential quarters and bludgeoned seven people to death with an axe. Among the dead included Mamah, her two children John and Martha, gardener David Lindblom, draftsman Emil Brodelle, workman Thomas Brunker, and Ernest Weston, another workman’s son. Following the rampage, Carlton tried to kill himself by swallowing hydrochloric acid; however, the suicide attempt failed. The madman was taken to prison where he died seven weeks later of starvation, the result of a hunger strike. Only two people on Taliesin’s campus survived the day.

Upon hearing the tragic news, a grief-stricken Wright returned to Taliesin to reassemble the shattered pieces of his livelihood. While reconstructing his retreat, Wright exchanged correspondence with a sculptor named Maude “Miriam” Noel. The two quickly established a romantic relationship and moved in together when Taliesin II was completed in the spring of 1915. The couple lived in Spring Green for less than a year before moving to Japan for five years. While in Tokyo, Wright designed the Imperial Hotel, arguably one of the architect’s most impressive feats. In addition to its visual appeal and lavish interior, the hotel was structurally sound. On September 1, 1923, just two months after the Imperial’s opening, the Great Kanto Earthquake—measuring 7.9 on the Richter scale—struck Tokyo and leveled over 80% of the city. Wright’s Imperial, however, managed to survive with only minor damages.

In 1922, Kitty finally granted Wright a divorce; however, he was required to wait a full year before marrying his then-mistress Miriam. In November 1923, Wright wed Miriam, but the marriage was tumultuous and short-lived. The two fought frequently over Wright’s infidelities and money troubles. Miriam also suffered from a severe morphine addiction, which caused her to be unpredictably violent and emotionally unstable (experts also suspect she had schizophrenia). The couple eventually separated in 1924.

Shortly after Miriam’s departure from Taliesin II, Wright found a new love interest—Olgivanna Lazovich Hinzenberg, a dancer from Montenegro. The two moved in together in early 1925 and had their first child, Iovanna, later that December. Like many of Wright’s prior relationships, this one was scandalous. Not only because Wright was still married to Miriam, but also because of the 31-year age difference between him and Olgivanna.

Scandal and incomplete commissions plagued Wright’s career between 1922 and 1934, as he was hard-pressed to find fulfilling work. Among the unfinished projects were the National Life Insurance Building (Chicago, Illinois 1924) and the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective (Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland 1925). The architect’s financial difficulties were further exasperated by poor spending habits, onset of the Great Depression, and cost of repairs from a second devastating Taliesin fire that occurred in 1925. By 1927, Wright’s finances had fallen into state of despondency. He tried to sell off his assets—including his extensive collection of Japanese prints—but was unable to pay his debts. The bank seized Taliesin later that year.

As if financial and occupational problems weren’t enough, legal troubles soon found their way into Wright’s life. In October 1926, Olgivanna’s ex-husband, Vlademar Hinzenberg, accused Wright of violating the Mann Act—which prohibited the transportation of women across state lines for “immoral purposes.” The loose language of the law placed Wright in a precarious (and potentially incriminating) position. While he was separated from his second wife, Miriam, the two were not divorced. And since Wright had a child with Olgivanna, their actions could be deemed “immoral.” The dejected architect was arrested in Tonka Bay, Minnesota, on October 20; however, the charges were later dropped. Miriam granted Wright a divorce in 1927, but Wright was again required to wait one year before remarrying. Wright and Olgivanna married in 1928.

Things began to turn around for Wright in 1932 when he established the Taliesin Fellowship—an experimental architectural apprenticeship program. The Fellowship was akin to an educational commune, as the curriculum integrated architecture and construction with farming, cooking, natural sciences, art, and dance. During the inaugural years of the program, Wright had virtually no commissions. Much of his apprentices’ time was spent doing agricultural work around the campus. Architectural instruction commenced in 1934 when Wright received a commission from Malcolm Wiley—a professor at the University of Minnesota—for several low-cost Usonian houses.

The Usonian Concept was the brainchild of Frank Lloyd Wright, first mentioned in his book The Disappearing City (1932). This innovative publication describes Broadacre City (Usonia)—a series of suburban developments comprised of Wright’s concept houses. Usonian structures were built without basements or attics and featured flat roofs to accommodate open-floor concepts. Wright wanted to facilitate the symbiosis of nuclear family mechanisms with his floorplans. Communal spaces—such as living rooms and kitchens—were open, interconnected, and centered inside the home. Private rooms, such as bedrooms, were often small and isolated. Wright believed this spatial disparity would encourage families to gather in the main living areas more often.

In November 1934, Wright became acquainted with Edgar “E.J.” and Liliane Kaufmann, whose son, Edgar jr., was an apprentice at his Taliesin Fellowship. The family owned the acclaimed Kaufmann Department Store—a thirteen-story downtown Pittsburgh galleria reported to be the largest in the world. While visiting Edgar jr. at Taliesin, E.J. asked Wright to design a weekend home along Bear Run, a scenic creek in the Laurel Highlands of southwestern Pennsylvania. Wright visited the proposed house site in December 1934 and agreed to the commission.

Wright made little progress on the Kaufmanns' concept home in the months following his Bear Run visit. One could argue he completely forgot about the commission. It wasn’t until September 22, 1935—when E.J. called to make a surprise visit to Taliesin and observe the plans—that Wright put a pen to paper. In what can only be described as an act of legend, Wright assembled his draftsmen and illustrated his vision in only two hours. Even the name “Fallingwater” was conceived on the spot, handwritten by the architect across the bottom of his design. When Kaufmann reviewed the plans later that day, he was initially shocked by Wright’s audacious design. Instead of placing the home across from Bear Run, Wright illustrated the structure directly over the cascading falls. This daring concept—inspired by the Kaufmanns’ admiration of Bear Run—allowed nature to be assimilated into the home. After several minor alterations, the preliminary plans were eventually approved by Kaufmann on October 15, 1935. The final blueprints were issued the following March.

Construction of Fallingwater began in April 1936 and was overseen by Robert Mosher, Wright’s Taliesin apprentice and on-site representative. The foundations were completed in July, then came the daunting task of cantilevering the structure over Bear Creek. Wright opted to use reinforced concrete to achieve this architectural effect, but given his inexperience with the material, Kaufmann was uncomfortable with the choice. He contacted an outside engineering firm who concluded that the weight of the concrete made the home structurally-unstable. Wright took offense to the notion and threatened to abandon the project. Kaufmann ultimately gave in to Wright’s impedance and the construction continued as planned. However, Kaufmann was right to question Wright’s decision. The concrete cantilevers developed a noticeable deflection as the structure settled. A supporting wall underneath the west terrace had to be constructed in order to maintain structural integrity.

Fallingwater was completed in the fall of 1937 and the Kaufmanns moved in later that December. In 1939, a guest house and spring-fed swimming pool were constructed on the property, connected to the main house by a cascading concrete canopy. The total cost of the 5300-square-foot home and its auxiliary structures was $155,000 (or $2.8 million today).

Fallingwater fully embodies Wright’s concept of organic architecture, seamlessly integrating nature with the human domicile. The southeast façade features a liberal use of glass to preserve an elongated view of the falls. Only sandstone columns and a central fireplace interrupt the continuous flow of the vista. The fireplace hearth, itself, is actually a large natural rock outcropping that protrudes from the foot of the living room. Also in the living room is a stairwell—covered by a glass hatchway—that leads directly down to the creek below.

The splendid design and execution of Fallingwater garnered Wright great fame. In January 1938, he was featured on the cover of Time Magazine. Later that year, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City dedicated a two-year exhibition to Fallingwater’s unique architectural concept, entitled “A New House by Frank Lloyd Wright.”

In 1937, Wright purchased 620 acres of land in the McDowell Mountain foothills near Scottsdale, Arizona. There, he established a permanent winter residence and architect studio called Taliesin West. Wright remained busy for the next two decades designing public buildings and private residences. The largest project during this time was the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. Commissioned in 1943, Wright spent nearly thirteen years drafting its abstract design before commencing with construction in 1956. The magnificent structure was completed on October 21, 1959; however, Wright would not be able to see his finished work. Frequent trips from Arizona to New York took a toll on the aging architect’s health. On April 4, 1959, Wright was hospitalized in Phoenix for a sudden illness. He died five days later at the age of 91.

After his father’s death on April 15, 1955, Edgar jr. inherited Fallingwater. With maintenance costs and preservation efforts being of increasing concern, Edgar jr. entrusted his family’s 1,500-acre estate to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy in October 1963. Fallingwater opened for public tours the following year and saw nearly 30,000 visitors. Today, this National Historic Landmark and UNESCO World Heritage Site welcomes over 180,000 tourists.

Visiting Fallingwater is an experience unlike any other. A basic guided tour package (around $32 for adults) takes guests on a captivating journey that comprehensively and intimately examines each room and terrace of the complex. Fallingwater’s interior remains virtually unchanged since the early 1960s, displaying the characteristic styles of modernism and contemporary cubism. In an effort to preserve these artifacts, interior photographs aren’t allowed. However, visitors are encouraged to as many photos as they please of Fallingwater’s illustrious exterior. Aside from the main house, the Fallingwater estate features several short hiking trails, convenient dining options, and enriching private event experiences. As one of the “most recognizable houses in the world,” Fallingwater is strikingly unique and unforgettable.

Visit the Fallingwater Homepage and Khan Academy to learn more about Fallingwater's history

Check out the Fallingwater Virtual Gallery to view the interior design and Kaufmann artifacts

Visit FrankLloydWright.org to read the famed architect's biography

Read more about the Taliesin Murders at History.com